The European Parliament’s Regional Development Committee today (7 September 2017) discussed the bi-annual report on the progress of EU Macro Regional Strategies. The UK is one of a minority of European Union member states that isn’t involved in one of these strategies. Now that Britain is on the road to leaving the European Union it is unlikely ever to do so, right?

Not exactly. The EU’s Macro-Regional Strategies are about co-operation between a group of nation states within a particular geographic area - and all the existing strategies involve countries that are not currently members of the EU (and in some cases which are unlikely to be any time soon). For example the Alps region involves France, Germany, Italy and Austria along with Lichtenstein and Switzerland from outside the EU.

The networks function very differently in different regions. This is admirably ‘flexible and imaginative’, as seems to be the phrase of the moment, and gives the lie to the notion that all EU policies and structures are handed down from on high in a ‘one size fits all’ way. In reality it isn’t like that. The Macro strategy regions work flexibly, set their own priorities and promote co-operation on the issues that matter to the countries in the region. They involve no new EU money, create no formal EU structures and neither require nor propose new EU legislation. This is all, in fact, a rather British approach. Unfortunately this type of network is exactly the kind of thing the UK has sometimes found it hard to understand in the past, although encouragingly over time UK local and regional bodies have become more and more engaged in similar kinds of structures.

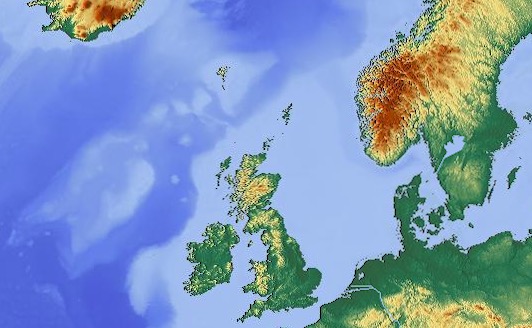

Of course the UK has been part of a region with excellent co-operation across the Channel, North and Irish Seas: the European Union. While I would of course like to see us remain part of that very effective union, if we are not going to then we should think about what new kinds of ties we can build with our neighbours. Not least Ireland (all of it) has a continued interest in getting through the UK to the other 26 states: then there’s all that fishing and marine conservation and now, sadly, border management to think about with a group of countries where English is almost universally spoken.

In the meeting, I made the point that UK may yet have a use for what might become EUSNAR (EU Strategic North Atlantic Region) that might comprise something like Belgium, The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Ireland with Norway, Iceland and the UK from outside the EU. If the Conservative Government of the UK had anything like a serious plan for leaving the European Union and establishing the ‘special and deep’ relationship to which its position papers pay lip service, it would be thinking about how such a relationship might be defined, in what way it might move forward and what forums it might take advantage of to help the process. Instead it shouts from the sidelines and tells its allies to ‘go whistle’.

The fact is in practice the UK, having sacrificed its considerable influence over EU policy, will need every channel available to mitigate the damage Brexit will inflict - so it might be wise to start the ball rolling as soon as possible.