Harold Wilson famously said, “If the Labour Party is not a moral crusade, then it is nothing”.

Harold Wilson knew very well, however, that the old way to deliver any aim, moral or otherwise, was through winning and retaining the power to do so. This author has made the point repeatedly that no political party has any right to form governments, lead the opposition or even to exist in a meaningful way. At the beginning of the pandemic the jury was out on Labour’s future, after the outcome of the leadership election the jury remained out and after more than a year of political stasis a verdict has yet to be reached.

If, however, Labour is to have a meaningful future its self-analysis has to extend well beyond the confines of who may of may not be part of its shadow cabinet. The unanswered question is what and who the Labour Party is for?

Some would say this is clear in Labour’s Constitutional Aims and Values. Others would say Labour is and always has been a ‘broad church’ party of the left. But that is not remotely sufficient for the situation in which we find ourselves. The need for a broad electoral coalition embodied within a single political party is a product of an electoral system that penalises third and smaller parties and rewards plurality disproportionately. Elsewhere, in more of less proportional systems, electoral coalitions are by degrees less necessary. Dependent on the voting system, electoral coalitions can fracture to the point where it is viable for parties to represent narrow interests and no party can realistically claim victory. Even if UK Labour had retained the support of its former base of the industrial working class it could not deliver its aims solely on that basis - they simply are not sufficiently numerous.

When successful Labour has constructed a articulated and in varying degrees delivered the material improvement of living standards of the majority - poor and not so poor, blue collar, white collar and professional. Labour has stood for optimistic self-interest of all people who work for a living. Families like mine voted Labour to improve our own lives. Labour since 2010 and to some extent before that retreated into a narrow and essentially pessimistic appeal to benevolence.

Without question Conservative-led Governments since 2010 have penalised the poor, increased inequality and used the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 as the excuse to dismantle a great deal of state provision. Without question it is a disgrace that in a developed and (still) rich country increasing numbers in the population rely on food banks, in fact it is a disgrace that the UK needs food banks at all. But it is also without question that those reliant on state provision and charitable organisation remain a minority lacking of themselves of any real political power and that their ‘mobilisation’ as such is a pipe dream.

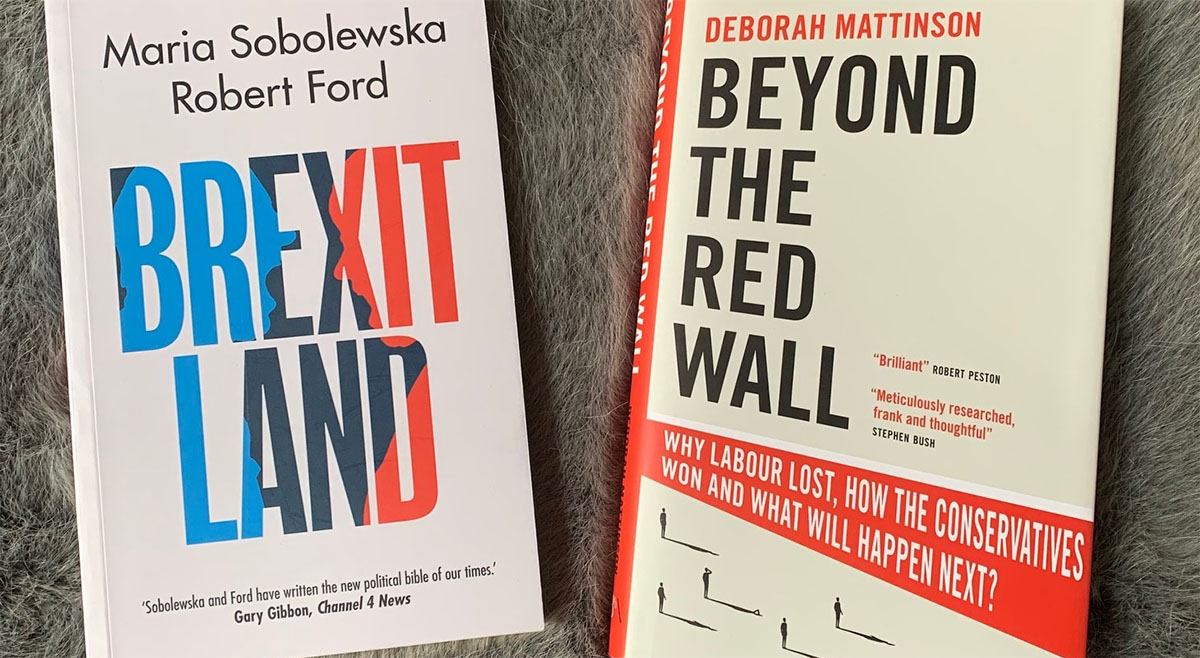

Poverty alleviation is without doubt part of Labour’s message and should always remain as such but delivering that outcome requires the votes of those who are not of do not see themselves as poor and who are primarily concerned with their own position. Some have argued that economic interests no longer apply, that ‘cultural’ rather than ‘economic’ issues now dominate political discourse. This is an argument made on the left and on the right equally. It has also been made by some who believe that the collapse of Labour’s ‘red wall’ support happened in spite of the apparently dire economic plight of many of those towns and semi-rural constituencies. That is a mis-reading of cultural and social trends driving votes in those constituencies. Politicians, myself included, who advocated remaining in the European Union did so in part because we believed it was objectively in the interests of working people and their families. However, it is quite clear from all research that a segment of working people were not persuaded of that view - their support for leaving the EU was not just about ‘Englishness’, migration or other cultural factors they perceived as in their economic interest, particularly so in ‘red wall’ (and ‘red wall’ like) areas.

The aspiration of ‘working class’ voters (C1s, C2s and D/Es if you prefer) for a more comfortable life, for a decent home of their own, for opportunities for themselves and their children - including those for whom University is not the best option, for access to good health and social care and for a neighbourhood in which they can take a degree of pride is as strong as it ever was. That desire may have found means of expression beyond the simply ‘economic’ but it has not gone away. The thing about recessions and depressions is that their effects are not uniform - ‘losers’ are a disproportionally hurt minority, ‘winners’ still make money and those in between seek to protect what they have. While the middle classes feel insecure an offer of radical change and with it further insecurity is even less appealing. Meanwhile in those small c conservative towns and villages the construction of new private housing estates goes on, as does the drift toward former industrial towns becoming affordable aspirational suburbs. While in 2019 Labour lost in places it had held for nearly a century, other bricks in the red-wall had been more recently marginal with Conservative MPs during the Thatcher era - Darlington, Hyndburn, Blackpool and so on. Not so much a return to the 30s as a trip back to the 80s.

There is no shortcut for Labour economic arguments have to reflect aspiration. There has to be ‘something in it for me’ and we have to be able to articulate the self-interest of a Labour vote. Poverty and a low-wage, casualised economy makes no sense for voters across a wide range of interests who look ‘not for a hand out but for a leg up’. Core policies need to address core concerns: fair pay in fair work, fair taxes that reflect the changed nature of the employment and contributory principles, pragmatic trade and security policies, local authorities with the resources and responsibilities to act and deliver pride in place. It is not the full picture but it is one of the essential elements without which ambition to change the country for the better will fall flat. It is also the only element that would enable Labour to re-unite the diverse elements of its vote that made it a plausible political force. Tilts toward social conservatism will never be enough, nor in any case are we those people - we need to be the owners of security, social and personal protection and the freedom to be yourself and make the best for yourself.

Self-interest will always be the motivating factor of the groups that in the UK’s system determine the outcome of elections - a system that isn’t changing any time soon. Labour forgot that and it has paid a massive price. Whether the party can re-learn it will determine the verdict once the jury returns.