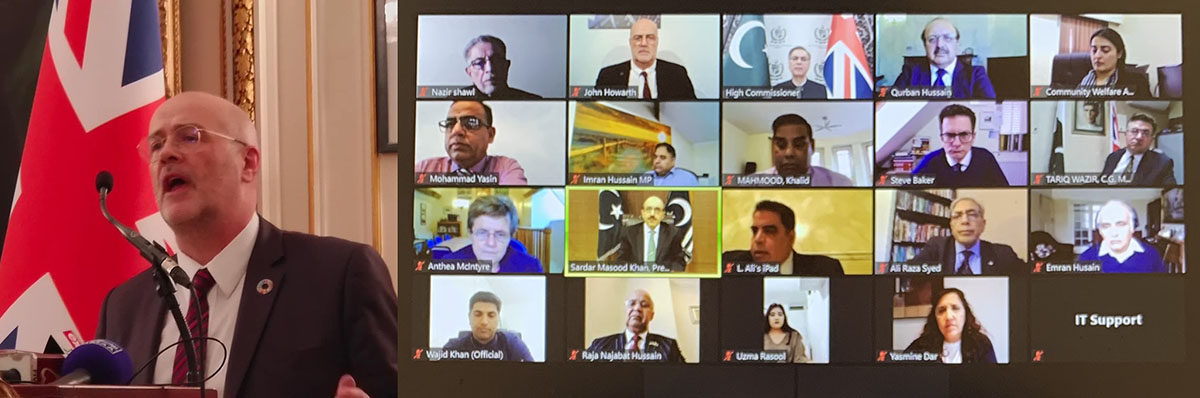

(Article re-published from 8 August 2020, above, At Kashmir Solidarity day, London Feb 2020 and EU Human Rights Kashmir Forum 27 October 2020)

It is 12 months since the protected status of the disputed territory in the Indian administered state of Jammu and Kashmir was revoked by the BJP Government of Narendra Modi. Since then disappearances, beatings, and other serial violations of the human rights of Kashmiris have continued, hidden from the gaze of the world by a state imposed black-out of the internet.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic hit the planet in February the Kashmir siege has become a double-lockdown. The vital role played by on-line information channels in seeking to combat the spread of Covid-19 has simply not been available to the Kashmiris. They have faced an imposed militarisation - the most intensive on the planet reportedly involving towards half a million Indian troops alongside a public health lockdown.

The irony of the removal of internet access should not be lost. The manipulation of the democracy indifferent internet by Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP in common with the tactics of populists and national conservatives around the world meant that the BJP government understood fully its importance. It is incumbent upon democrats and progressives to help ensure the flow of information to opinion leaders is maintained and truth is spoken to power on this entirely unacceptable situation.

The response of the international community to the latest episode in a dispute seven decades old has been predictably weak. It is a weakness amplified by the continued undermining of multilateral institutions by the likes of Donald Trump. Until it is recognised that the strengthening of the international community is essential to producing brokered solutions the prospects for progress in Kashmir and the in the 39 other disputed regions around the world are grim.

However there are levers to pull and there are actions that can be taken. The desire of the UK for trade arrangements present an opportunity to raise the necessity for respect for human rights - Ms Truss is likely to discover that India is a difficult place to conclude such arrangements. UK politicians can nonetheless use the opportunity to highlight how the actions of the BJP government are damaging India’s international reputation. The message should be simple – the situation in Kashmir is bad for business, standing in the way of economic development in the South Asia region.

Elsewhere the European Union represents a much greater prize for India but also a jurisdiction where trade deals are openly scrutinised by MEPs and where progress on human rights is key to their conclusion. The same rules must apply to India as have been applied to other trade treaties. In this conflict it remains open to the EU either to be a force for good or to ignore the problem. Friends of democracy and human rights can help ensure the former both in the EU institutions and among the governments of the 27 member states.

Behind the changes to the status of Jammu and Kashmir last August several things ought to be clear.

First, it is hard to see, given a population of ten million, how the notion of promoting ‘settlement’ in the Jammu and Kashmir with the intention of changing the demographic can be sustainable. Unless, of course, the policy is accompanied by another policy of ‘removal’ and the deliberate creation of a refugee crisis on a massive scale. We would all naturally hope this is does not come to pass - but just hoping genocide will not become policy has not always worked elsewhere.

Second, there is no military solution to the problems of Jammu and Kashmir. Like conflicts elsewhere, it has not and will not resolve the issue and that fact must be recognised by all parties as an essential step toward peace. De-escalation is more important than ever, the presence in international observers is more important than ever, demilitarization and the deployment of international observers is urgent and is the most significant step toward improving the lives of Kashmiris and respecting their human rights.

Third, there is no solution to the Kashmiri dispute without the involvement and consent of the Kashmiris themselves. This truth should be self evident, sadly it has evaded many in positions of power and powerful vested interests.

Finally, it is simply not good enough to dismiss this conflict as ‘an internal matter’ for India any more than the plight of the Rohingya is an internal matter for Myanmar or the persecution of the Uighur is solely the concern of China. Neither is it sufficient for it to be dismissed as a bi-lateral matter for India and Pakistan. Kashmir, like those tragedies, is a matter for humanity.