A landmark result and a real setback

The predicted headlines came to be printed. The ‘Brexit Party’ had swept to victory. Nigel Farage had ‘won’ the 2019 European Parliament Election. The stalled project of national self-harm was confirmed as the ‘will of the people’. Britain had voted for Brexit again.

Or had it?

Once the facts are analysed only the most superficial reading casts the result as an unequivocal endorsement of Brexit. However, not for the first time the reporting of a UK election result was pre-conceived, shallow and inevitably misleading. What really happened in the 2019 European Parliament Elections was quite different to the shallow propaganda of the pro-Brexit press. The calm voice of psephology among the headless chickens, Professor John Curtice, summed it up like this:

“Alas, ... care and circumspection ... sometimes seemed in rather short supply in the immediate wake of the declaration of the results as those on all sides of the Brexit debate attempted to argue that the results showed that most voters supported their outlook on Brexit. They could not, of course, possibly all be right.”

So what really happened? And what does Labour need to do to win back the votes it has lost?

Facts and Fictions

Both the Faragistas and the Remainiacs (for want of a better term - more on that later) set out to play the European elections as a ‘proxy referendum’; Farage had been peddling his betrayal narrative since shortly after the polls had close in then 2016 referendum. Sadly the Liberal Democrats chose to play the Brexiteer game and positioned themselves as the ‘remain’ option in the proxy plebecite. This position suited Farage but was always a flawed strategy for remainers because, well, it wasn’t a referendum.

- Referendum: binary question,

- EP elections: multi-party, proportional choice. Not the same.

- Turnout at the 2016 referendum: 72.2%. Turnout at the 2019

- EP elections: 37%. Just over half. Not the same.

There may have been only one reason for voting for the Brexit Party, but hard though it may be for some to understand, there were more reasons for voting Green, for example, than their opposition to Brexit. Equally, not everyone who voted Conservative did so out of enthusiasm for Mrs May’s failed settlement. There was, however, only one reason for voting for the Brexit Party. So while the results tell us something about the support for ‘leave’ and ‘remain’ positions they are indicatoras rather than conclusions.

So what truths do the numbers tell us?

Remain parties outscored Leave Parties

In a proportional election voter loyalty to the big UK parties is weakened. Unlike ‘first past the post’ there are few, or at least many fewer, ‘wasted votes’, so the ‘no point in voting Green/LibDem/Labour/Tory’ argument doesn’t really apply. Accordingly voters are much more likely to reflect their view through the ballot box rather than vote ‘for’ or ‘against’ a Government or opposition.

As a result ever since the proportional-ish system replaced the single constituency system in 1999 each European Parliament election has brought out those most opposed to the EU while those who don’t really care that much have stayed at home. For opponents of the EU and/or Britain’s membership the EP elections were not about deciding how the EU should be run but to vote against Europe’. In 2014 UKIP, knawing at votes of the other parties, topped the poll.

In 2019 the Brexit Party would reasonably claim that a vote fo r them was a vote for Brexit. It is also fair to assume that the residual vote for UKIP 1.0 is a vote for Brexit, along with those for fringe far-right elements in various regions. Less reasonable it the contention that a vote for the Brexit Party is a vote for a ‘no deal’ exit - it is hard to argue that some Brexit Party voters at this election would prefer to leave with a deal but were expressing frustration that the UK had not yet managed to leave the EU.

On the other side of the fence the only reason anyone was given to vote for the Liberal Democrats was to “stop Brexit”. Their positioning was voting LibDem = voting remain. While it is true there were reasons other than opposing Brexit to vote for the Green Party, the demographic of their vote is firmly ‘remain’ - it is reasonable to count their votes as anti-Brexit. Change UK made ‘remaining’ their reason for existence, so they have to be counted with the remain total. The SNP, Plaid Cymru, Sinn Fein and the Alliance Party in Northern Ireland have consistently adopted a remain stance (though SF had argued support for Mrs May’s settlement) .

On this basis the (Brexit Party, UKIP and the DUP) garnered 5.9 million votes (34.9% of the vote). The ‘remain’ parties (LibDems, Green Party, Change, the SNP, Plaid Cymru and others) totalled 6.8 million (40.4% of the vote).

It is pretty hard for Mr Farage to claim that the vote for his UKIP upgrade has a clear meaning while more votes for people clearly opposed to his view somehow has none. Whatever else Britain voted for it clearly did not vote in favour of leaving the EU without a deal.

This remains true when Labour and Tory votes are added

The Labour and Conservative parties suffered badly and their vote shares, already diminished by the effects of proportionality, were squeezed hard by the ‘proxy plebecite parties’. The most logical interpretaction of a Labour or Conservative vote at these elections was that those voters are just supporters of those parties who just always vote that way. This doesn’t mean they didn’t necessarily believe Brexit was important, just not as important as supporting their party.

So while on the face of it might seem reasonable to assume that the Conservative vote was a vote for Mrs May’s version of Brexit, in reality many of these voters simply always vote that way - they would split in favour of Brexit, certainly, but not entirely.

Evidence suggests that voters deserted Labour for the LibDems, the Greens and to a lesser extent the Brexit Party. Those who stayed with Labour did so largely because they were Labour voters come what may. We know from consistent polling evidence that Labour’s vote splits heavily in favour of ‘remain’ but again not entirely. Precisely because these voters are ‘core’ voters - they are the most likely to follow the lead of their party come another referendum. Whatever machinations may yet go on it is hard to see in the case of a second vote the Conservatives now calling for anything other than a Brexit vote and Labour calling for anything other than remain. For this reason as much as any it is a reasonable assumption that these core voters largely cancel each other out otherwise could be counted Conservative for ‘leave’ and Labour as ‘remain’

On this assumption in Great Britain the ‘leave’ parties totalled 42.5% and the ‘remain’ parties 53.7% (the other 3.8% being made up of fringe outfits and Northern Ireland (which was and is clearly pro-remain). The mean of Great Britain 55.8% leaned toward remain and 44.2% toward leave - a swing of 7.6% from the referendum on a much smaller turnout but nonetheless looking rather like much of the recent opinion polling.

Farage did not win as big as he wants you to believe

The performance of the Brexit Party itself compares poorly with the post-election bombast of Farage. The Brexit Party vote was 30.5% of the turnout - only 3.9% higher than UKIP 1.0 in 2014. Adding in UKIP 1.0 at 3.2% that came to an increase for the ‘hard Brexiteers/‘no dealers’ of 7.1%, yet the Conservative share was down 14.3% - so where did the other half go? Clearly not to Labour, but to Change, the LibDems and the Green Party - explicitly pro-remain parties. So despite this ‘great betrayal’, the detox of UKIP 2.0 and the single policy, the Brexit Party and UKIP managed to get 5.8 million voters - just one in three of those who voted to leave - to ‘tell them again’. 12% of the electorate - equivalent to roughly 18% of the referendum turnout - is just not an endorsement of anything.

In every region of the UK the ‘leave’ parties polled a lower combined share of the vote than the share ‘leave’ reached in the 2016 referendum. In several the outcome tipped from ‘leave’ to ‘remain’ - Wales, North West, South West and South East England. In only Scotland and North East England was the combined vote of the right of centre parties (Brexit, UKIP and Conservative) higher than that at the 2014 European Elections.

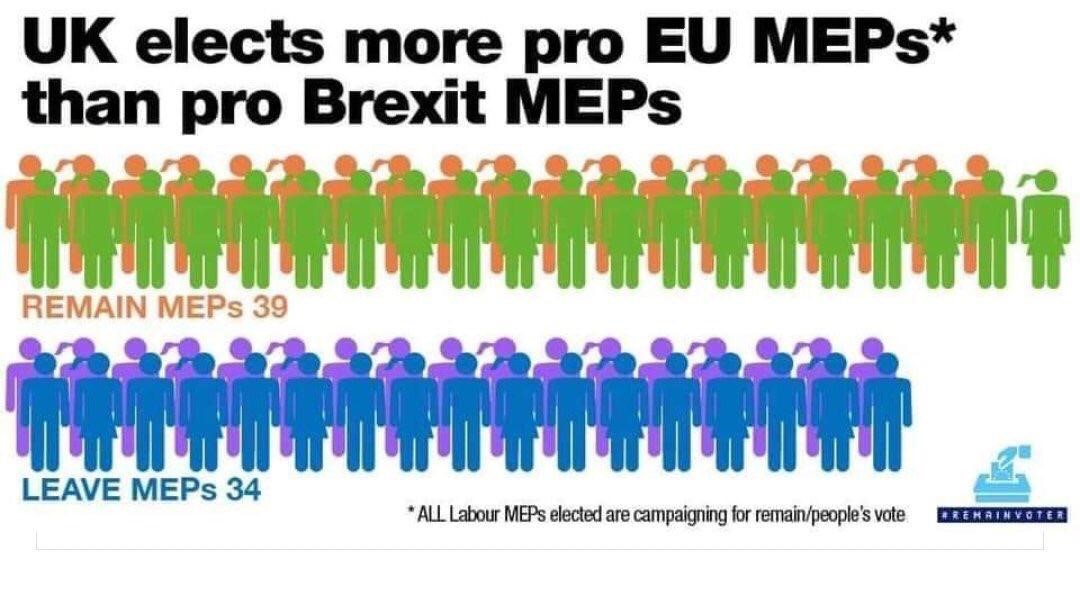

By no credible criteria was the 2019 European Parliament election a vote of confidence for Brexit. There are now 39 MEPs supporting a public vote with the option to remain and 34 supporting Brexit. Once again, not what anyone rational would call ‘winning’.

The Brexit Party’s 'success' has already shifted the Tories further right

However perceptions are often more important in politics than reality. The narrative of a Brexit Party victory and a Brexit frustrated electorate driving Conservative defeat in local elections has certainly helped to drive the Conservatives further toward a ‘leave at any cost’ position. The perception, aided by the volatile evidence of Westminster opinion polls, that the Conservative Party faces electoral oblivion should it ‘fail to deliver Brexit’ has spooked the Conservative centre and emboldened the right. It has also given Mr Farage leverage over the party many of his former UKIP 1.0 members have re-joined or infiltrated. Now he threatens de-selections, electoral opposition and vote splitting. Boris Johnson, strengthened by ‘no dealer’ entryism, makes a naked appeal to the party interest over the national interest in his leadership pitch. A deeper examination of the results of 27 May seems to have eluded most Tories caught like rabbits in the Brexit Party headlights or prepared, according to internal surveys, to sacrifice many a former sacred cow on the alter of Brexit.

What drove the result?

Brexit Party: An effective strategy

Let’s not underestimate what Mr Farage pulled off, with a little help from some exceedingly gullible journalists. As an exercise in ruthless political re-engineering it was remarkable, as a branding exercise stupendous, and the clarity of the message pretty much faultless. The Brexit Party campaign was as good as Labour’s was bad. As a comms guy/strategist/marketeer/spin doctor of 30 years (choose your epithet/insult as you wish) I have to take my hat off to them. None of this, however, changes the reality. It does not make them right, or good, or rational or anything really other than UKIP gone to rehab. Control of the message is easy when you don’t engage, gaffs are easy to avoid when there is only one face to keep on message, policy is beyond scrutiny when there isn’t any policy to scrutinise, members don’t embarrass you when there are no members, and as for sitting MEPs - why on earth should they get to play (other than the odd one or two). All this suits Mr Farage, noticeably reluctant to share the limelight at the best of times, down to the ground.

It also passed off largely without challenge. ‘A party set up only five weeks ago’ - technically true, but really just a re-brand of UKIP because UKIP was always just Nigel and Nigel was always UKIP. When Andrew Marr provided some semblance of challenge it was dismissed by Farage as ‘proof of BBC bias’, when Channel 4 exposed Mr Farage as “a kept man” once again he didn’t engage, when questions are raised about murky finances they are dismissed by Mr Farage because ‘people don’t care about that stuff’. So the spectacle of a bunch of rich men passing themselves off as ‘anti-establishment’ continued as the same old piss in a shiny new bottle. Underperformance is easily dismissed as in any case ‘remarkable for a party only five weeks old’, etc - expectation management and spin.

Tories: Chasing Unicorns

Aside from paralysis and panic the debate among Conservatives has been taken backwards in the aftermath of 27 May. The contest for the conservative leadership boiled down to two candidates conducting a bidding war over UK public policy and the Brexit settlement. After a baffling array of incompetents and oddballs were whittled down both of the final candidates promised both deal and no deal to their potential followers. They each promise that by charisma, determination, smarm or just by asking nicely some kind of ‘better deal’ with the EU27 can be produced after the failure of Theresa May to do exactly the same thing on a timescale universally accepted by anyone who knows as utterly ridiculous. The notion is entirely absurd yet, having been proved as such, is being rolled out again.

Einstein’s observation that madness is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results is not just part of the UK’s malaise, under the Conservatives it has become public policy.

LibDems: The national by-election

The Liberals, their Alliance with the ill-fated SDP and their LibDem successors were most successful as the recipients of protest votes at UK parliamentary by-elections. This came to a screeching halt after their coalition agreement with the Conservatives in 2010. The European Parliament Elections of 2019 saw them fighting a by-election on a national scale. Without doubt the LibDems spotted the opportunity to rehabilitate themselves with an electorate sceptical of their broken promises an long-term support of the economic austerity of the Conservatives. It was fought with a clear, simple message despite their self-evident inability to deliver their promise to ‘stop Brexit’.

In England, the LibDems did best in strong ‘remain’ areas, eating heavily into the Labour vote. However, it is worth noting that these areas tended to have something else in common - they did best in areas where they had a presence on the ground - those parts of the country where they gained heavily in council elections four weeks previously. In those areas where the LibDems have little organisation the ‘remain’ vote stayed with Labour in greater numbers. This by-election on a grand scale, was one where the chattering classes chattered that ‘this time everybody is voting LibDem’.

Chatter was a factor - but less so where the LibDems were not organised. The very fact that Brexit has been constantly in the news meant that people were talking about the elections. The turnout was up 1.4% on 2014 - which was co-terminus with local elections in much of the UK - and this for an election which was not meant to happen and where MEPs were not meant to take their seats. The Green Party did proportionally better where they had previously failed to trouble the scorers - the north and midlands of England, but may have done better had they not struggled against the LibDem assertion to be the vote to ‘stop Brexit’. Fishing in the same pond were Change UK, of which little should be said other than it is fast becoming a textbook study of how not to launch a political party.

Labour: Unfinished business

Labour’s share of the vote fell by between one third (in London) and by two thirds (in Scotland) from the last European Elections. Labour seemed to hold its share most effectively where its ground organisation was strongest (and conversely the LibDems weakest) and where the black and ethnic minority vote was most significant. In Scotland, comparison with the last European Election is not equivalent to England and Wales because of the post-2014 referendum legacy. Labour, while facing a squeeze from both sides post-election polling (asking people how they voted rather than how they intended to vote) shows that Labour lost only a small share to the Brexit Party and massively more to the LibDems and Green Party. It should be noted that Labour has always lost support to the Green Party in European PR elections but rarely to the LibDems.

Labour’s problem was political. While it is true that it is a great deal easier for a minor party to make a promise it can’t actually keep on something like ‘stopping Brexit’, Labour’s NEC, who set the policy for the election, failed for whatever reason to grasp the obvious - that there was simply no political space for Labour’s position of ‘bringing the country together’ as the voters believe there is unfinished business. Under such circumstances to fail to complete the move toward a re-consideration of Brexit was electoral suicide. Labour’s dilemma ahead of the next General Election is well summed up by an activist on the campaign trail who said to me while pointing at LibDem posters:

“We had wiped out the LibDems round here. They’ve not been seen for years - now look, they are back.”

The problem is when people stop voting Labour it is often a challenge to get them to start again.

Where that road map when you need it?

The elections scared the Conservative Party and, if anything, seem to have made it even more pro-Brexit and near enough guaranteed a hard Brexiteer in Number 10. For Labour the outcome was a major defeat snatched from the jaws of victory. As things stand neither Government nor Opposition looks capable of winning an election with anything like a convincing share of the vote. The consequences for the UK of a Government that patently lacks public support and moral authority thrown into Downing Street on the back of the quirks of first past the post are potentially very serious. All that probably means an election is less likely than many observers surmise.

But when the election comes it will still be fought under that maligned and discredited system and it is essential that a real choice is put before the country. For first past the post to work it requires two large broad coalitions providing that choice. To recover from its worst result in 100 years Labour needs first of all to listen to its voters and to restore the faith of those members who have remained on board, though I fear in truth it may be too little, too late. If Labour is to come through this the only possible road is to support the public vote on the Brexit settlement, argue remain and reform. If that is beyond some in the high command then they need to move over for someone who can do so convincingly. Without this neither the party nor the country will be able to move on.

The election was a step on the road the Brexit Party are treading - it was a battle in the greater war of winning the real second referendum. They saw and understood the opportunity and they took it. Farage has already said he would work with Johnson in a no-deal electoral pact. However the outcome also showed that Brexit - the concept not just the Party - can be defeated.

Furthermore, the elections fractured the de-facto remain alliance that had developed since the 2016 referendum. The Liberal Democrats were prepared to sacrifice that to restore the electoral fortunes of their party. Their objective, reasonably accomplished, was to harness the ‘remainiac’ vote - they were not changing minds, merely providing an outlet for frustration and self-righteousness. The fact, however, is that minds need changing and the way the Liberal Democrats go about the issue turns off all but the most convinced.

But despite the short-term success of the LibDems, their resurgence won’t and can’t ‘stop Brexit’. Something more and something less arrogant is required. So painful as it may be that alliance must be repaired and a strategy for winning a public vote, rather than just fighting for one, implemented - and fast. That strategy must go beyond feel good statements and flag waving toward taking on the problematic notion of how we see ourselves as a nation in 2019 and debunking the concept that Britain ever won anything by ‘standing alone’.

Photo: campaigning in Brighton during the campaign that never was.